Original post by Benjamin J. Hulac of Roll Call

All politics are local, Senate Republicans’ environmental politics included.

In the South, Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., favors a ban on offshore oil and gas drilling. In the West, Sens. Cory Gardner, R-Colo., and Steve Daines, R-Mont., highlight their work on a new law that permanently funds the Land and Water Conservation Fund, a federal pool of money from oil and gas royalties, and provides $9.5 billion over five years for the National Park Service to knock off its backlogged list of maintenance projects.

In Alaska, Republican Sen. Dan Sullivan on Aug. 24 came out against the Pebble Mine — a proposed copper and gold project in the state’s southwest near Bristol Bay, home to the world’s biggest wild salmon run — after the Army Corps of Engineers determined the project would not meet permit requirements under federal water law.

As the country reels from scorching fires and smoke-obscured skies in the West as well as hurricanes, tropical storms and flooding in the East and South, Senate Republicans up for reelection are hewing to local environmental issues rather than focusing on national climate policy in an attempt to woo moderate voters on Election Day. The strategy could help separate them from President Donald Trump, whose administration has weakened or eliminated scores of environmental rules and climate protections.

“I think that’s the winning strategy for elect or for reelect,” said Heather Reams, executive director of Citizens for Responsible Energy Solutions, a right-leaning clean energy group. “Being very specific and hyperlocal, I think, is the winning ticket,” she said, adding that she would coach Republicans running for office to ignore national trends. “What matters is what’s going on at home.”

Alex Conant, a partner at Firehouse Strategies, said, “Republicans are talking about the environment more than they ever have before,” in part to reach independent and younger voters.

“Republicans see the environment as a way to reach out to independent voters without turning off their own base,” said Conant, a Republican campaign veteran and former communications director for Florida GOP Sen. Marco Rubio’s 2016 presidential race.

Republicans lost the House in 2018 amid a surge of independent, female and suburban voters, many of whom cast their ballots for Democrats in a rebuke of Trump.

A 2019 survey by Nexus Polling, with help from researchers at Yale and George Mason universities, of more than 8,600 voters nationally and in six swing states — Florida, Michigan, Iowa, Texas, Ohio and Georgia — found climate change was a top priority for Democrats and Democratic-leaning independent voters.

Climate and environmental issues can be links to independent and female voters, citizens born in the 1980s or later, and suburban voters — a bloc critical to Trump for reelection.

“Any areas to bridge into those segments of the population would be wise,” Reams said, counting climate or environmental preservation as ways to contact independent voters.

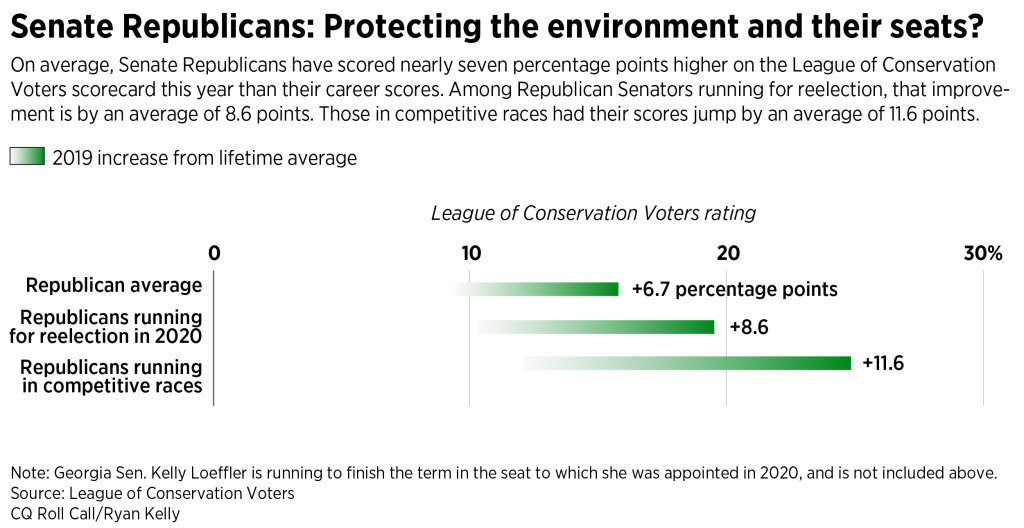

Vulnerable Republicans have been inching toward more eco-friendly résumés this Congress, according to metrics from the League of Conservation Voters, which tracks members’ voting records on environmental issues and rates them accordingly. (A higher percentage means a more eco-friendly record.)

Of the 20 GOP senators running this year, 15 raised their scores in 2019, the latest year available, from their lifetime scores in Congress.

Big bump

Considered one of the two most vulnerable Senate Republicans — along with Arizona’s Martha McSally, according to Inside Elections with Nathan L. Gonzales — Gardner bumped his score up to 36 percent in 2019, a sharp climb from his 11 percent lifetime rating, which includes his House tenure.

Corina McKendry, a Colorado College political science professor and director of the environmental studies program there, said the spike from GOP candidates reflects a “realization on the part of some Republicans that there is bipartisan support for conservation and the environment.”

Plus, she said, running on environmental policies could counter Democrats’ abilities to use the Trump administration’s deregulatory environmental record in campaign advertisements.

McKendry said it might be “valuable” for Republicans to distinguish themselves from the Trump administration, which has weakened at least 95 federal rules on the environment, according to the Environmental Integrity Project, a watchdog group.

“In Colorado, this is clearly the case,” McKendry said. “Support for public lands is very strong, and Gardner clearly knows that.”

In July, seven Republican senators — including at-risk incumbents Gardner, Graham and McSally, as well as Susan Collins of Maine and Thom Tillis of North Carolina — pressed Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell to include aid for “clean energy” industries in upcoming coronavirus relief legislation.

At a recent campaign-style rally in Florida, where he signed an executive order freezing offshore oil and gas drilling in Florida, Georgia and South Carolina, Trump declared himself the best president for the environment since Theodore Roosevelt, an architect of the National Park System.

“It’s true: No. 1 since Teddy Roosevelt. Who would have thought Trump is the great environmentalist?” Trump said. “That’s good. And I am. I am. I believe strongly in it.”

Trump followed on Sept. 14, while surveying wildfire damage in California, by disagreeing with the head of the state’s natural resources department, Wade Crowfoot, over science.

“It’ll start getting cooler,” Trump said.

“I wish,” Crowfoot replied. “You just watch,” Trump said. “I wish science agreed with you,” Crowfoot answered. Trump said, “Well, I don’t think science knows, actually.”

Science does know. Humans are raising Earth’s temperature by burning fossil fuels and through deforestation and modern agriculture. Despite that, Trump’s administration has scaled back or eliminated 161 climate mitigation or adaptation rules since 2017, according to the Climate Deregulation Tracker from Columbia University’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law.

Trump separation

Alluding to 2016, when Senate Republicans largely outperformed the president, Conant said GOP candidates this year can separate themselves from Trump. “It definitely can be done,” he said. “And one way you do that is by championing local issues,” he added. “I can’t think of a better one than the local environmental issues.”

Yet Trump undercut that strategy with his anti-scientific rhetoric in California, Conant said. “Not only does he undermine the agenda, he undermines every vulnerable Republican. The well-educated suburban women who are going to decide this election have very little tolerance for climate denialism.”

Kyle Kondik, managing editor of Sabato’s Crystal Ball, a nonpartisan newsletter from the University of Virginia’s Center for Politics, said climate change is more sharply partisan than environmental stewardship.

“Someone like Cory Gardner and Steve Daines can talk about preserving nature in states where a lot of people do outdoors activities,” Kondik said. “There may be ways to say certain things that you’re doing that broadly could be considered as pro-environment without advocating for massive government intervention on climate change.

“In some ways, clean rivers and clean lakes and open space are sort of like grandma and apple pie. No one’s going to be campaigning for pollution.”

Running on climate could be a way to swing independent voters to members like Gardner, who represents a state the president lost in 2016, Kondik said.

“It could be a way to present yourself as someone who is a different kind of Republican and someone who is able to demonstrate some independence from the party,” Kondik said.

Because greenhouse gases are invisible and climate change is a subtle crisis that steadily unfurls, it can be hard for the public to grasp the threat. Local environmental crises are often easier for candidates to spotlight, Kondik said. “Sometimes it can be more salient if there’s some sort of specific project or issue that will directly affect people’s lives.”

Citing Rep. Joe Cunningham’s race in 2018, when the freshman Democrat from South Carolina campaigned against coastal oil drilling and flipped a seat Democrats had not held for nearly three decades, Kondik said, “It’s easier to understand the stakes of a specific project.”

Megan Jacobs, national campaigns director at the League of Conservation Voters, said the uptick in LCV scores for incumbent Republicans is a smokescreen.

“This is totally greenwashing,” Jacobs said. “These last-minute actions to greenwash their record and try to paint themselves as environmental champions aren’t going to work.”

Reams said the parties discuss environmental issues differently, with Republicans often approaching the topics through a local, business-centric lens. She pointed to McSally’s support of solar power in Arizona. “The love language of climate and environment is very different for Republicans than it is for Democrats,” Reams said.

Iowa gets the largest percentage of its energy from wind power of any state, and in a March interview, Sen. Joni Ernst, R-Iowa, touted wind provisions included in a Senate energy bill from Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska, chairwoman of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee.

“Nearly 40 percent of the electric that we draw and use in Iowa is from wind energy,” Ernst said.

Asked if climate change was hitting farmers in her home state, Ernst avoided that term.

“We call it conservation in Iowa, and we’re very serious about conservation,” she said.